Rocks in Canada Are Confirmed as World’s Oldest

In 2008 scientists reported that rocks in Canada were the world’s oldest. New data appear to confirm this contested claim

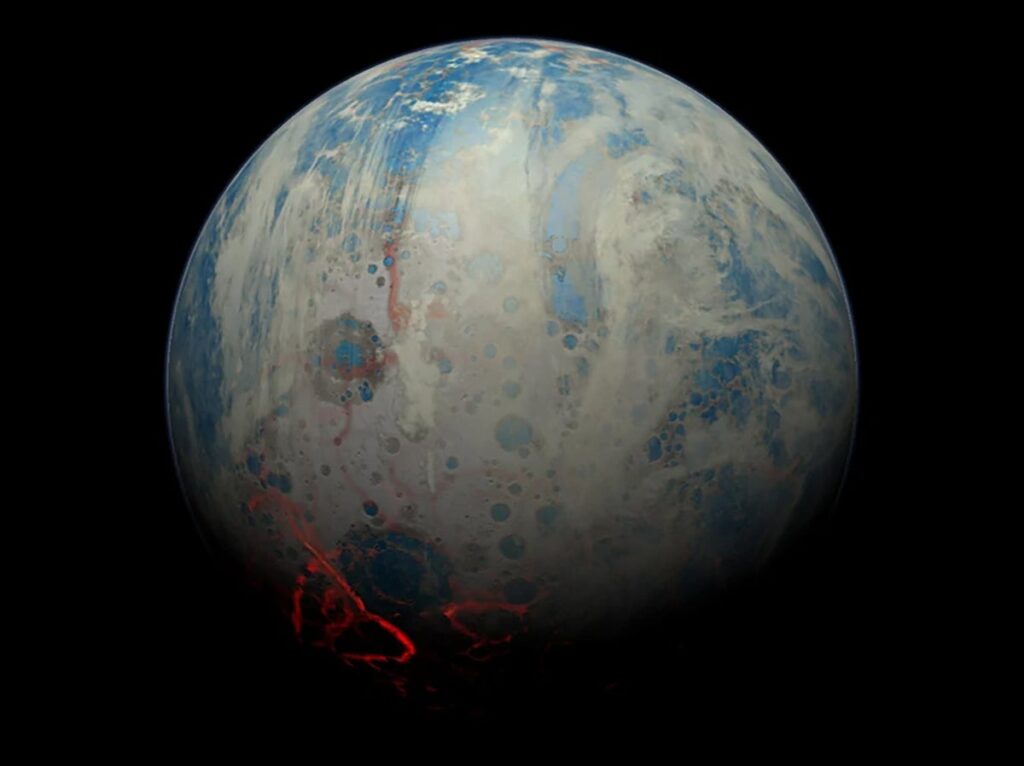

An artistic impression of Earth during the Hadean eon, when the planet formed its first solid crust—most of which later sank into the mantle never to be seen again.

On the shores of Hudson Bay in northeastern Canada lie what could be the world’s oldest rocks. A study now suggests they are at least 4.16 billion years old — 160 million years older than any others recorded, and the only piece of Earth’s crust known to have survived from the planet’s earliest eon.

In 2008, researchers reported that these rocks dated back 4.3 billion years, a claim that other scientists contested. Work reported today in Science1 seems to confirm that the rocks, known as the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt, are record-breakers.

Researchers say the rock formation offers a unique window into early Earth, after the planet cooled from its fiery birth 4.5 billion years ago.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“It’s not a matter of ‘my rock is older than yours’,” says Jonathan O’Neil, a geologist at Ottawa University who leads the research team. “It’s just that this is a unique opportunity to understand what was going on during that time.”

The ‘oldest rocks’ label has sometimes backfired. In the past few years, other teams have chiselled many samples out of the Nuvvuagittuq belt, leaving the landscape scarred. Last year, the local Inuit community closed access to the rocks to prevent further despoliation.

Only a handful of geological samples in the world date back to 3.8 billion years or older. Of those, the oldest undisputed rocks are found in the Acasta gneiss formation in Canada’s Northwest Territories; at 4 billion years old, they mark the boundary between Earth’s first geological eon, the Hadean, and the following one, the Archaean. Geologists have also found tiny mineral crystals dating back to the Hadean — such as 4.4-billion-year-old zircon crystals from Western Australia — that have become embedded into newer rock. But there are no known surviving chunks of crust from the Hadean — except, perhaps, the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt. It consists primarily of material that started out as volcanic basalt before undergoing various modifications during Earth’s tortured history.

The dark rock of Canada’s Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt could have originated from the basaltic lava of a volcano that erupted some 4.3 billion years ago.

In their 2008 work, O’Neil and his colleagues analysed the chemical imprint left by the radioactive decay of the isotope samarium-146 into neodymium-142 to calculate that the Nuvvuagittuq rocks were 4.3 billion years old. (Samarium-146 is a short-lived isotope that was depleted in Earth’s first 500 million years, and none was left after about 4 billion years ago.) Other scientists challenged that work, arguing, for instance, that Hadean-age crust had become mixed into younger crust, contaminating the results.

For the latest work, O’Neil’s team analysed some once-molten rocks that had intruded into the main Nuvvuagittuq rocks like a knife cutting into a cake. By dating the intruded rocks, O’Neil and his colleagues were able to establish a minimum age for the cake itself. They used two radioactive clocks: the decay of samarium-146 into neodymium-142 and that of samarium-147 into neodymium-143. Both yielded ages of around 4.16 billion years for the intruded rocks. “If you don’t agree with this, then you need a very speculative, intricate model to get to the same answer,” says O’Neil.

Having both clocks agree on an age — which wasn’t the case in the earlier work — strengthens the case for a Hadean age for the rocks, says Bernard Bourdon, a geochemist at the University of Lyon in France. He remains circumspect, though, and says he would like to see additional lines of evidence, involving other radioactive isotope decays. “I would be happy if these rocks were truly Hadean, but I think we still need to be cautious,” Bourdon says.

The paper “provides a new data set that hopefully can advance this discussion”, says Richard Carlson, a geochemist at Carnegie Science in Washington DC who has collaborated with O’Neil in previous work. To Carlson, the bulk of the evidence suggests that the rocks are indeed Hadean.

For now, more answers might have to wait. The Pituvik Landholding Corporation in Inukjuak, Canada — the Inuit group that is steward of the land in question — is not currently granting permits for further scientific study, due to the earlier damage by other groups. “It’s unfortunate, but I would do the same,” O’Neil says.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on June 26, 2025.