Kersplat … thwack … thunk … wham!

There’s nothing quite like a summer road trip and the hail-like sound of bugs hitting your windshield and leaving a streak of splatter.

The blobs are icky but they also leave identifiable patterns.

Mark Hostetler, a wildlife biologist, noticed how messy his windshield would get, especially in May and September, during “lovebug season” in Florida.

Dr. Hostetler, a professor of wildlife ecology and conservation at the University of Florida, said the bug glop can coat windshields during those peak times, forcing drivers to pull over to do a cleaning.

During one of his own stops in the 1990s, he realized that the goo on his car could become a teaching tool.

He began identifying the sticky remains.

His windshield became a laboratory, and now yours can, too.

1 of 5

Dr. Hostetler began his own education in the field of “splatology” by heading to a Greyhound bus station in Gainesville, Fla., and then to Greyhound bus depots across North America.

The large vertical bus windshields made it easier to identify the splatter because parts of the insects would stick, he said.

At night, Dr. Hostetler plucked bug carcasses from buses after they returned to their stations from being out during the day.

2 of 5

No matter the terrain, bugs will find you, Dr. Hostetler said. You might find more cicadas near forested areas, and more butterflies and moths on roads near open areas and meadows.

Insects, especially moths, are attracted to headlights. They confuse the lights with moonlight, which they use as a compass.

The lovebugs that first caught Dr. Hostetler’s eye are found in the southeastern United States. They’re called lovebugs because they’re busy making love while in flight — and stuck together midair — during their four‐day life span.

This makes it challenging for them to see where they are going. It’s no wonder that they end up smushed on windshields.

It was so bad in the late 1960s and early ’70s that drivers in Florida had to stop every 10 miles to scrape them off.

3 of 5

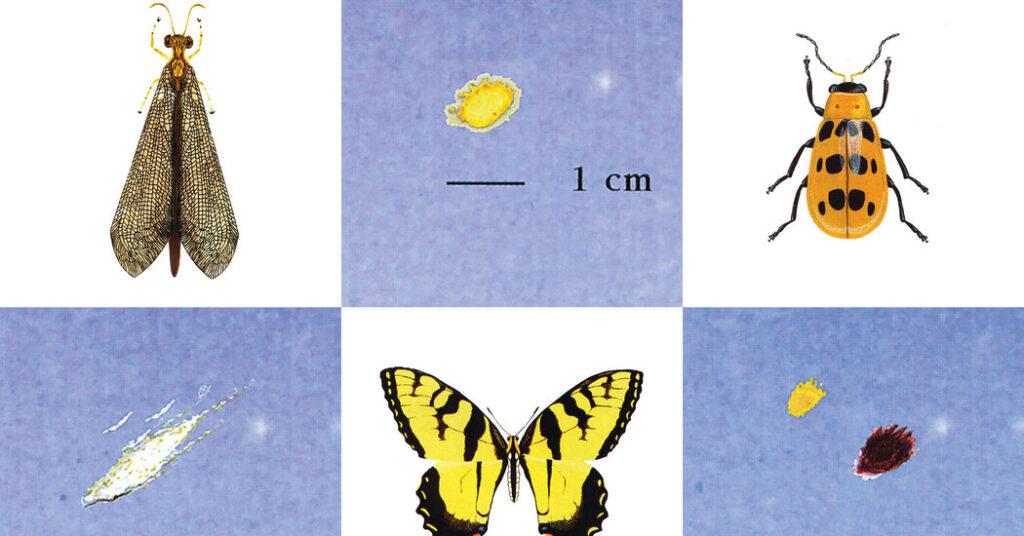

Dr. Hostetler identified 24 types of bugs, and he found an illustrator, Rebekah McClean, to create colorful drawings to match the insects with their splatter.

They compiled their work into “That Gunk on Your Car: A Unique Guide to the Insects of North America.”

Dr. Hostetler’s son, Bryce Hostetler, built and released a free app, “That Gunk On Your Car.” It has the contents of the book, which lists critters, their characteristic splats, fun facts about each bug, and car games.

While it’s all educational and fun, it’s also challenging and imprecise.

The splats are tiny and measured in millimeters. It’s easy to mistake one insect for another, especially when there are thousands of kinds of butterflies and moths.

The splatter’s form can depend on the speed and shape of your car, specifically the windshield angle.

Dr. Hostetler advised that it’s best to wash off the creamed remains as soon as possible, before they dry, and to use elbow grease with soapy water and “a sponge with a little mesh on it for scrubbing.”

4 of 5

Bug guts are not quite snowflakes — of which no two are alike — but they can look that way to a novice.

Dr. Hostetler’s aim is to get people to think more about the critical role that insects play in the environment and in the food chain.

“If we got rid of all our insects, the whole ecosystem would collapse,” he said.

5 of 5

Other scientists have noticed fewer bug splatters than in past decades and refer to the decline as the windshield phenomenon.

Their hypothesis is that a drop in vehicle bug splatter signals a decline in the insect population.

Beyond this anecdotal indication, there is much more scientific research suggesting that insects are in the greatest existential crisis in their 400-million-year history.

The population of monarch butterflies, for example, dropped to the second-lowest level on record at their overwintering areas in Mexico last year. Industrial agricultural practices — habitat destruction and pesticide use, in particular — were to blame, scientists suggested.

No scientist blames vehicles for the precipitous decline in insects, though it can look that way after a summer road trip.

As Mary Chapin Carpenter sings, “Sometimes you’re the windshield; sometimes you’re the bug.”