Plague is often associated with Medieval history and the centuries-old Black Death epidemic, but a recent death in northern Arizona is a troublesome reminder of the flea-borne disease’s lingering hold in parts of the world, including the U.S. Local health officials in Arizona’s Coconino County, which includes the city of Flagstaff, confirmed late last week that a person there had died of pneumonic plague—a severe lung infection caused by Yersinia pestis, the bacterium behind the illness.

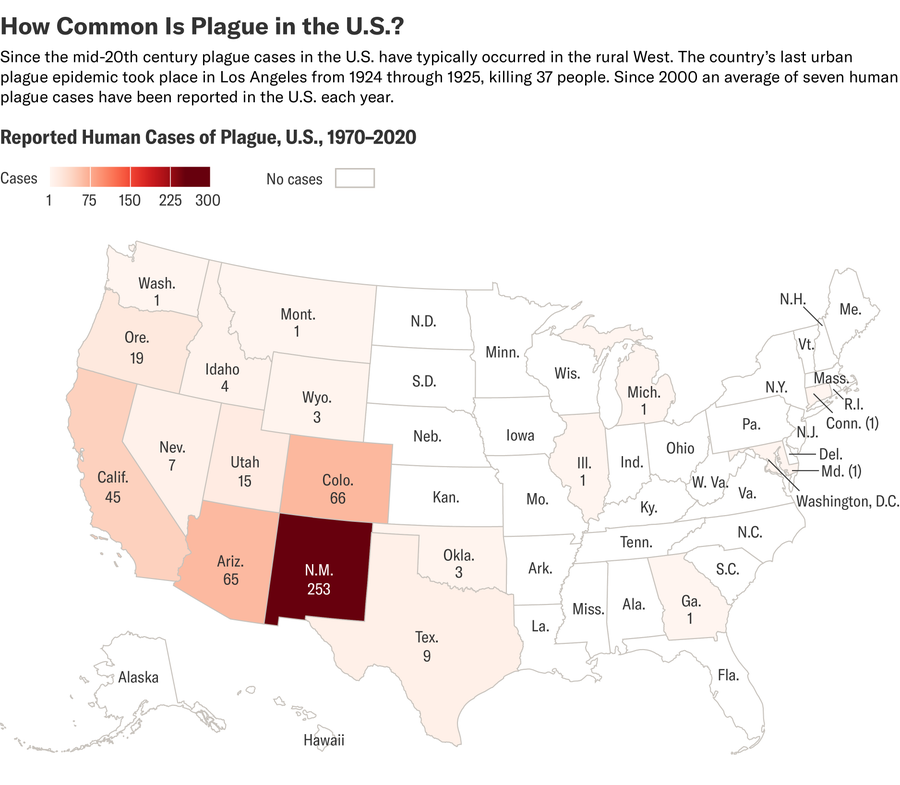

Human infections and fatalities from plague are relatively rare in the U.S.; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, seven human cases are reported annually on average. Prior to the Arizona case, the most recent death was reported in 2021. Y. pestis arrived in port cities in the U.S. around 1900 and has since become endemic to rats and other rodents in western U.S. states including New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, California, Oregon and Nevada.

“From a public health standpoint in the U.S., it’s a scary thing that it’s plague, and it’s tragic that that this was a fatal case, but people need to remember that it’s extremely rare,” says David Wagner, executive director of the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute at Northern Arizona University, who has studied plague for more than 25 years. “Not to be flippant, but it’s more important that you put your seat belt on going to the grocery store than it is to worry about plague in the western U.S.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Scientific American spoke with Wagner about plague’s signs and symptoms, and its persistence across time.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

How do people get sick with plague?

Plague is caused by the bacterium Y. pestis and is really a disease of rodents and their fleas. You have an infected rodent; a flea feeds on the blood of that rodent, and it picks up some Y. pestis. Then when the flea feeds on another rodent, it can pass along the Y. pestis. It’s constantly cycling back and forth between rodents and fleas in nature; that’s how it’s been maintained for thousands of years in the environment around the world.

What’s the difference between bubonic and pneumonic plague?

People call it the Black Death; they call it bubonic plague; they call it pneumonic plague—it’s all the same disease, just different clinical manifestations. What stands apart [with the recent case is] that it’s pneumonic plague. That’s kind of rare, especially in the U.S.

Pretty much all human cases, with a few exceptions, are acquired from the environment—from the bite of an infected flea. If there isn’t a rodent host for that flea to feed on, it will look for other mammals to feed on. And if humans happen to be in proximity, it will feed on humans and can transmit Y. pestis.

If the immune system doesn’t stop Y. pestis at the source of the flea bite, it will migrate through your lymphatic system to your closest major lymph node. So let’s say I was bit on my wrist; then the bacteria would go to that lymph node in my underarm and start to reproduce there. And that mass swelling, that swollen lymph node, is called a bubo—that’s why it’s called bubonic plague. These days, it’s a dead end because there’s not flea-borne transmission from one human to another. It just stops there with the treatment or death of that individual.

Left untreated, though, bubonic plague can get down into your lungs via the bloodstream. That’s called secondary pneumonic plague. Those individuals, then, via cough or direct contact, can spread plague person-to-person, and that’s called primary pneumonic plague.

What people might not know is that plague has been endemic throughout the western U.S. in rodent populations for more than 100 years.

Someone could also get pneumonic plague from an animal—for example, if they were handling an infected animal and that animal coughed. Sometimes hunters in Central Asia will kill [infected] ground squirrels, and when they’re skinning them can inhale particles. People also talk about septicemic plague, and that means it’s gotten into your bloodstream, and that typically also arises from bubonic plague. You could also get [septicemic plague] directly if you had cuts on your hands and were handling rodents without gloves.

Can pets get infected or transmit plague to humans?

Pets, especially free-roaming ones, may come into contact with dead rodents that have died of plague. Fleas can hop onto pets, which then bring them into the home. This is pretty rare because there are so few [human] cases in the U.S., but that is something we think about.

Flea and tick collars are a good idea. If animals do get sick, most of the evidence shows that dogs fight off the infection and can create antibodies against Y. pestis. Cats are more susceptible and can quickly become sick and actually can progress to pneumonic plague. It’s super, super rare, but that’s a possible way for humans to be exposed to pneumonic plague.

What are the symptoms and treatment?

With bubonic plague, typically people develop a fever, headache, chills and fatigue, and then they’ll get those swollen lymph nodes called buboes. It typically takes a few days to manifest because it sort of starts off in stealthy mode inside the body to try and avoid the immune system.

Plague is easily treated with many different types of antibiotics, as long as it’s caught in time. If untreated, bubonic plague mortality rates may be somewhere between 30 to 60 percent, depending on the situation. Pneumonic plague, left untreated, is almost always fatal. So diagnostics become really important. The challenge is that many physicians in the U.S. have never seen plague. The symptoms are a bit common to other things, so rapid testing in the lab can help.

Where is plague typically found in the U.S. and around the world?

What people might not know is that plague has been endemic throughout the western U.S. in rodent populations for more than 100 years. It just so happened that a lot of the rodent host species in Central Asia, where it evolved, were quite similar to some of the ground squirrels that we have here in the U.S. It was first reported in native ground squirrels in California in 1908 and was in human populations before then. And then it spread really rapidly to the east and just sort of stopped at the western edge of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. It’s a bit of a mystery why; the rodent diversity and climate changes quite a bit in [that region].

I’m also currently working on plague with colleagues in Madagascar, which has more human plague cases than any other country—around 75 percent of the global [case] total. It has hundreds to thousands of cases every year, with quite a few deaths.

How has it persisted over the years?

We don’t have a good handle on which rodents are actually maintaining it in the U.S. So we’ve been going out and collecting plague-infected fleas from prairie dogs for more than 25 years because it’s our window into plague activity. Prairie dogs are ground squirrels that live in dense colonies, so they’re very conspicuous. If the prairie dogs die off, we go out and collect fleas from their burrows. We take a piece of white flannel, breathe on it to bait it with carbon dioxide, and then put it down the burrows. The fleas will hop on, and then we take them back to our laboratory and freeze them to kill them. Then we can study the Y. pestis DNA directly from those fleas. We’re very careful when we do this, and we talk with our physicians here at Northern Arizona University. Every year we review the symptoms and they give us a prescription for antibiotics. Then we do what we call fever watch, where we take our temperature before we go out.

The prairie dogs can’t be maintaining it because they’re just so susceptible—it’ll just wipe out a whole colony when it gets in. And so there’s other rodents out there maintaining plague, but it’s still a bit of a mystery in the western U.S.

How has it become less dangerous?

There were three great historical plague pandemics, and it’s estimated that maybe 250 million people died [total]. But we don’t have those large pandemics anymore because we have hygiene, which controls rat populations in cities—and then, most importantly, we have antibiotics.