‘Corn Sweat’ Is Making This Heat Wave Even Worse

Humid heat is blanketing the eastern U.S. this week, exacerbated by “corn sweat” in the Midwest

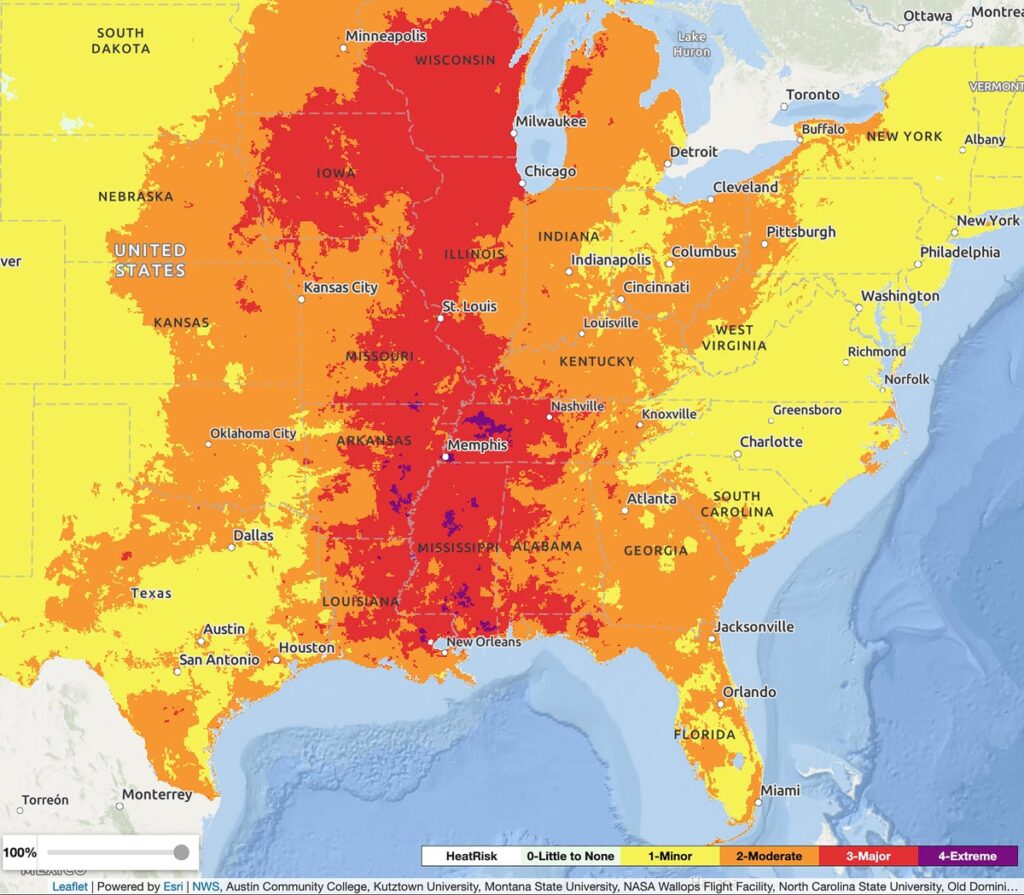

The HeatRisk forecast for July 23, 2025.

National Weather Service/NOAA

Heat and humidity will once again smother the eastern half of the country this week, pushing the heat index to dangerous levels for tens of millions of people. In the Midwest, the humidity will be boosted by a phenomenon called “corn sweat.”

It’s midsummer, so heat and humidity are pretty standard in the wetter eastern half of the country. It’s unlikely this heat wave will break records, but it could still be dangerous, says Bob Oravec, lead forecaster at the National Weather Service’s office in College Park, Md.

[Read more: Heat Is More Than Just Temperature—Here’s How We Measure It]

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

On Monday the heat and humidity are centered over the Southeast and along the Gulf Coast. By midweek, they will move northward along the Mississippi Valley and up into the Midwest before they shift toward the mid-Atlantic and Northeast around the end of the week. Highs are expected to be around 95 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit (35 to 38 degrees Celsius) as the heat wave moves along, but the humidity means it could feel closer to 110 degrees F (43 degrees C) in the most affected areas. Large swaths of the eastern U.S. will be in the “major” HeatRisk category, a NWS classification that incorporates heat, humidity and data on when heat-related hospitalizations tend to rise in a given area. Pockets will be in the “extreme” category, the highest on the four-category scale.

Part of the reason for the oppressive humidity is that “the weather pattern has been favorable for wet weather,” Oravec says. “Everything is wet, saturated,” which means there is more evaporation from soil and transpiration from plants. This is particularly true in the Midwest, where huge fields of corn, soybeans and other crops release moisture as the temperature climbs. The process is akin to how humans perspire in the heat, hence the nickname “corn sweat.” “The Midwest is famous for high dew points from the vegetation,” Oravec says.

Plants aside, the phenomenon has serious implications for humans. High humidity and heat raise the risk of heat illness—it is harder for the body to cool itself via sweating because the air is already so full of moisture that perspiration doesn’t evaporate. Those concerns are especially high for at-risk groups such as young children, older adults, those who have various health conditions or take certain medications, people who work outdoors and unhoused people.

Prolonged exposure to such conditions can result in heat exhaustion, which can cause fatigue, dizziness, nausea and a cessation of sweating. If a person with this condition doesn’t get to a cooler location or receive treatment quickly, heat exhaustion can progress to heat stroke, which causes the body to lose its ability to cool itself, an extremely dangerous situation. In fact, it can be fatal.

Experts caution people to stay hydrated and avoid strenuous outdoor activity, especially in the middle of the day, when temperatures are highest. There are also tips for keeping your home cool. [Read more: Six Ways to Stay Safe Outdoors in Extreme Heat]

These concerns will linger both in the short and long term. In the long term, heat waves are becoming hotter and happening more frequently than in the past because of the added heat trapped by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as a result of humans burning fossil fuels. An analysis by the nonprofit Climate Central found that human-caused climate change made this extreme heat event at least three times more likely for nearly 160 million people, almost half of the U.S. population.

In the short term, weather models show humid heat over the eastern U.S. for the next week or two. “The weather pattern is just kind of stagnant and is stuck,” Oravec says. “It looks like it’s going to be a hot few weeks.”