One day in 1989, Dutch magazine editor Derk Sauer asked his wife if she fancied moving to Moscow, where he had been offered a job. “Can’t we go to America?” she replied. Still, they moved with their baby into a cockroach-ridden flat in a city of bread queues.

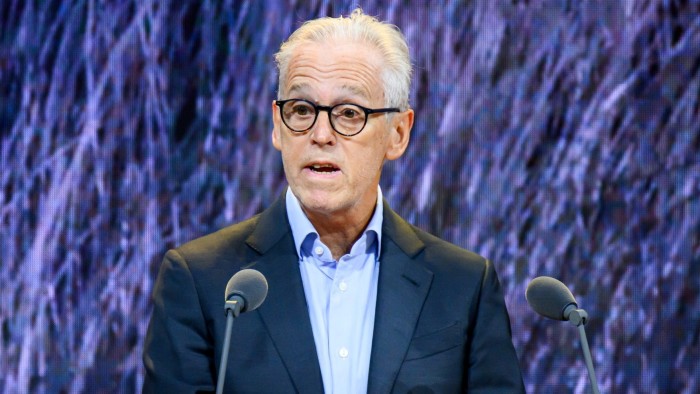

Over the following decades, Sauer — who has died aged 72 after a sailing accident — fell for Russia, and became a Moscow media magnate, a rare westerner to make his fortune there. In the early 1990s, he founded The Moscow Times, an English-language news outlet that endures to this day, as well as the Russian editions of magazines including Cosmopolitan and Playboy.

He started life on Amsterdam’s Stalinlaan, which was later renamed after the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. He rebelled against his conservative father, who ran a pension fund, but identified with his mother’s cousin, a wartime Resistance hero.

Sauer founded the “Action Group for World Peace”, aged 14, demonstrated against the Vietnam war and became a Maoist, prompting the Dutch intelligence service to spy on him for nearly 20 years. Reading his file later, he commented: “Half the information was wrong.”

Snubbing university, he tried to join the working class and briefly worked in a chewing-gum factory. But he preferred journalism. He had presented a national TV programme, aged 16, and in 1970 set up as correspondent in Northern Ireland, where, he later admitted, he also smuggled weapons in his car for the paramilitary Irish Republican Army. “Obviously they were used for attacks,” he told Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant in 2013. He later rejected the IRA, saying he realised it was chiefly a mafia.

He spent the 1980s editing the Dutch weekly Nieuwe Revu with his winning formula of “sex, news and rock & roll”. But he found life too easy in his quiet home country. When an official delegation of Russian journalists (including KGB agents) came looking for a Dutch business partner, someone suggested the “communist” Sauer. It was an offer he could not resist.

On February 24, 1990 he drove to Russia in a car packed with basic necessities. Knowing the horror stories about Russian hospitals, the Sauers even brought their own blood plasma.

The born journalist proved a born businessman, too. A giant market with almost no consumer products was an entrepreneur’s dream. His Dutch biographer Dido Michielsen wrote that Sauer’s appearance — he was a tiny man from a small country with a friendly smile — lulled people into complacency, allowing him to achieve his ends. “If I have one talent, it’s that I can make something happen,” Sauer told De Morgen in 2011.

In 1992 he launched the English-language The Moscow Times newspaper initially based at the Radisson Slavyanska hotel, where he resembled a bespectacled scoutmaster among his eager young journalists.

Two years later, his company, Independent Media, started a Russian edition of Cosmopolitan magazine, edited by his wife and fellow journalist, Ellen Verbeek. The small editorial office operated out of an apartment building, according to his biographer. To keep nosy neighbours from asking too many questions, Sauer initially cleaned the office and toilets himself.

He said Russian Cosmo became Europe’s bestselling magazine. Readers would phone to say, “Thanks to you, I finally left my drunken husband.”

Sauer launched Russian editions of dozens of magazines including Playboy, Men’s Health and, his personal passion, Yoga Journal. Together with partners including the Financial Times, he co-founded the business newspaper Vedomosti. He said his newspapers were small enough that the regime left them alone. Independent Media offered western-style newsrooms and professional standards for generations of Russian journalists.

The Sauers eventually moved into the wealthy Moscow suburb of Zhukovka. With three sons in local schools, they socialised with the Russian elite. In his shaky Russian, Sauer conducted a delicate dance with the country’s biznesmeny, doing deals while trying to avoid danger. This was not easy: after Russian Playboy’s editor was shot (he survived), Sauer went around with bodyguards for years.

But he made it. He became a multimillionaire in 1998, selling shares in Independent Media. Sauer, Verbeek and their business partner Annemarie van Gaal celebrated with a shopping weekend in Paris, then went back to work. In 2005 Finnish publisher Sanoma bought Independent Media for €142mn. Sauer shared some of the proceeds with his staff, “from drivers to directors”, according to The Moscow Times’ publisher Alexander Gubsky. Sauer’s own wealth eventually peaked at €70mn, estimated Dutch business magazine Quote.

He also founded a Dutch publishing house, Nieuw-Amsterdam. (Disclosure: it has published my books.)

Sauer told his biographer he morphed over time “from socialist into journalist”, and from youthful gunrunner into “pacifist yogi”. He backed the far-left Dutch Socialistische partij, saying, “I’m not against wealth, I’m against poverty”.

He deplored Vladimir Putin’s growing authoritarianism, but stayed in Russia for the deep friendships, long winters with cross-country skiing, and daily excitement, wrote Michielsen. Dutch people saved for old age, Russians lived for now. He recounted his adventures in a weekly column in Amsterdam’s Parool newspaper.

Sauer ran the media group RBK until the authorities forced him out in 2015. In 2017 he bought back his beloved Moscow Times. It and Vedomosti were “the little lights of independent journalism still burning”, he said, in his old-fashioned Amsterdam accent, frozen in time after decades abroad.

He divided his Moscow life into three periods: “unlimited optimism” in his first years, followed by “unlimited consumption”, and then “cynicism”. But on February 24, 2022 came horror, with the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Putin cracked down on the last independent media. Sauer fled Russia, writing on the day following the invasion: “I am ashamed not to have warned enough against the tyrant of our time.” Two years later, he teared up on Dutch TV after Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny died in a Siberian prison.

Separated from Russia, Sauer felt the deep Russian sadness known as “toska”. Yet with undimmed energy, he helped move The Moscow Times and other independent media to Amsterdam, persuading Dutch authorities to accept a contingent of 150 Russian exiles. This year he launched a music label for Russian artists banned at home.

He died after injuring his back when his sailboat hit an underwater rock. He is survived by his wife Ellen, his three sons who dream in Russian, and The Moscow Times.