Every Monday and Tuesday morning, Bosede Oluwaokere, 48, wakes up at home in Ilorin city in west Nigeria, gets dressed and walks to a nearby stream. She sits beneath a tree and pulls her skirt up around her thighs. For the next six hours she stays in the same spot waiting for a specific type of fly to land on her, so she can catch it using a small plastic tube.

Oluwaokere is a human flycatcher – or human landing catch, as the World Health Organization (WHO) terms it – which is considered the “gold standard” for collecting black flies. Black flies, which breed near rivers, are blood-sucking insects that spread the debilitating neglected tropical disease onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness.

When someone is bitten by an infected black fly, the larvae of the parasitic Onchocerca volvulus invade their body and grow into worms that can live for up to 15 years. Female worms produce thousands of microscopic larvae that spread throughout the body. If the larvae reach the person’s eyes, it can cause permanent loss of sight.

When black flies suck the blood of an infected person, they can then pass it on to someone else they bite.

“I like this work,” says Oluwaokere, who was recruited as a volunteer by the health ministry. “I’m not scared to do it, because I love my community and I want it to be free from disease.”

She is paid a stipend of 10,000 naira (just under £5) a month by Sightsavers, an international health charity.

In Nigeria, about 40 million people are at risk of onchocerciasis. There are 120,000 cases of related blindness in the country, and many thousands suffer from disabling complications of the disease.

According to the WHO, in 2023 almost 250 million people required preventative treatment against onchocerciasis around the world. More than 99% of infected people live in Africa and Yemen; the remaining 1% live on the border between Brazil and Venezuela. The Global Burden of Disease Study estimated in 2017 that 14.6 million of the infected people already had skin disease and 1.15 million had vision loss.

The WHO road map for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) identified onchocerciasis as one of the diseases targeted for elimination and set ambitious targets to be reached by 2030.

There is no cure for onchocerciasis, but the WHO recommends mass drug administration (MDA), where large numbers of people are given medication to prevent its spread. The current treatment is donated by the pharmaceutical company Merck under the brand name of Mectizan. It is administered to at-risk populations once or twice a year for up to 15 years. As more people are treated, and fewer are infected with the disease, black flies become less likely to pass on the parasite.

after newsletter promotion

After several rounds of MDA, health ministries in affected countries conduct tests to determine whether they can declare they have eliminated the disease. First, people in at-risk areas have finger-prick blood tests to see whether they carry the disease. Then, black flies in endemic areas must be tested to see if they are still carrying the parasites. In Nigeria, the target is to test 6,000 black flies. But first they have to be caught and human flycatchers are the preferred method.

For years, there have been ethical concerns around using people as bait for research purposes. “It makes me quite uncomfortable as it’s a risky practice,” says Louise Hamill, director for onchocerciasis at Sightsavers. “We are asking a human being with a family, a life and a job, to put everything on pause and go and sit beside a river for [a significant chunk] of the day. They are putting themselves at high risk for black fly bites, but also they’re outdoors so they could get bitten by a tsetse fly and get sleeping sickness, or by a mosquito and get malaria or dengue fever. They could be bitten by a snake, exposed to lots of direct sunlight, sunburn, heat, rain.”

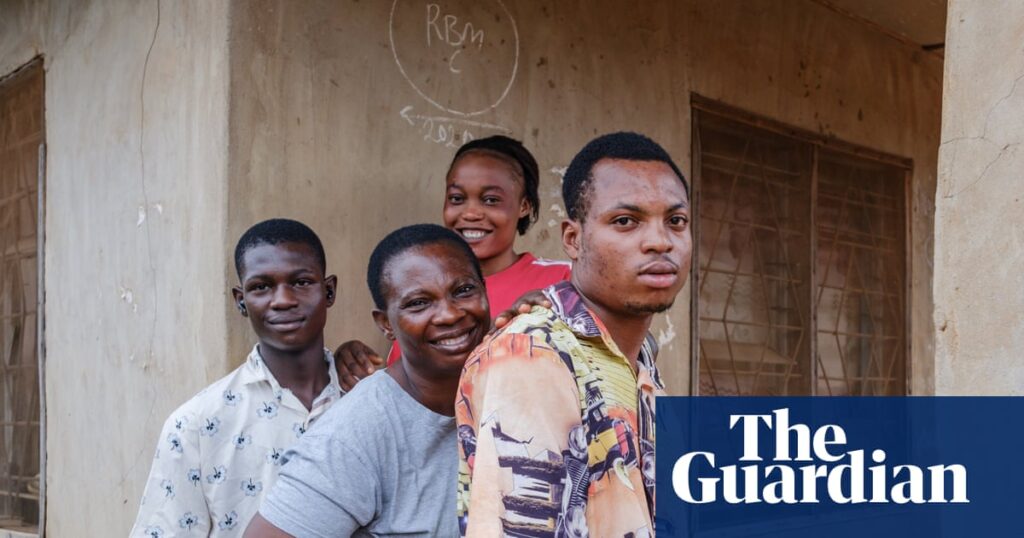

Oluwaokere is undeterred by such risks, but her fellow volunteer, Olamilekan Adekeye, a 26-year-old university student who does the afternoon shift after her on a Monday and Tuesday, had to flee after seeing a black snake. “I don’t know what type of snake it was, but fear made me run away. I hid in a nearby shop and came back a few hours later.”

The WHO also recommends using Esperanza window traps (EWT), where flies are caught on sticky surfaces, to catch black flies. They were first proposed as a method to collect the flies in 2013. Although they have worked well in South America, they haven’t been as effective in Africa.

“I think it’s because of the human factor,” says Dr Maria Rebollo Polo, lead of the global onchocerciasis elimination programme at the WHO. “The attractiveness of humans to the flies seems so powerful that it’s difficult to imitate.”

To avoid using people, Sightsavers and the Global Institute for Disease Elimination are working on developing and optimising EWTs. Research in Malawi, Mozambique, Ghana and Ivory Coast, due to be published this year, is looking into deploying variations of the traps that use carbon dioxide to mimic human breath, different coloured glues and clothes, and even the simulated smell of sweaty feet.

Rebollo says that human flycatchers, despite being a “rudimentary [research] technique”, are still used because of a lack of funding. “Obviously if neglected tropical diseases attracted more interest and if we had more resources, then we would, by now, have better techniques that would reduce any potential human discomfort,” she says.

But she argues that humans are required for multiple research purposes, such as blood tests on children to monitor malaria or clinical trials where people are exposed to medicines. In each country there are ethical committees that determine whether, and how, people should be used in research purposes.

Back in Ilorin, Oluwaokere and Adekeye are happy to be able to contribute to possible advances in health, but they would love to be paid more. “The amount of money I receive is too small,” says Adekeye. “I have other sources of work which pay better, but I choose to do this to help my community.”