What Books Scientific American Read in July

Check out Scientific American’s fiction and nonfiction book recommendations for July

Fernando Trabanco Fotografía/Getty Images

July 2025 has been a sweltering month, but we at Scientific American have still squeezed in some fun in the sun and a hot dog or two, all while choosing the best books to read poolside. We’ve been busy exploring new science books. This month we read science-backed advice from one parent to another; met a robot with seriously snarky sentience; uncovered the global black market for trash; and traveled to the ends of the Earth, where scientists are discovering the history of the planet—and a glimpse into our future.

What are you reading this summer? Sign up for our daily newsletter Today in Science to get exclusive weekly reading recommendations and share your booklist.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Hello, Cruel World! Science-Based Strategies for Raising Terrific Kids in Terrifying Times

by Melinda Wenner Moyer

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, May 2025

The world seems to have gotten meaner—or just harder to raise kids in. Ensuring they’re ready to combat escalating climate change, growing political turmoil and dangerous online misinformation hasn’t made things any easier. Thankfully, parents can turn to science-backed strategies to help prepare their kids for a complicated future. For her new book, Hello, Cruel World! science journalist Melinda Wenner Moyer talked to experts for evidence-backed tips for helping young people cope with challenges, connect to others and cultivate strong character. In an interview with Scientific American, Moyer said that to help children develop savvy news judgment, nearly “every media literacy expert” recommended this approach: ask them open-ended questions about the media they watch—such as “What do you like about this show?”—or, for bigger kids, more complex queries—such as “Who might benefit from this? Who might be harmed by it?” And how should parents respond when kids actually answer these big questions? Drop everything and just listen, even when you disagree, Moyer said. —Brianne Kane

The Murderbot Diaries series

by Martha Wells

Tor Books, 2017–present

The season finale of the television series Murderbot aired in early July on Apple TV+, concluding the first season of the buzzworthy adaptation of Martha Wells’s beloved science-fiction novella series The Murderbot Diaries. But I couldn’t help but wonder: Would the titular Murderbot enjoy the TV show? In Wells’s books, Murderbot (a cyborg security unit assigned to scientists on a dangerous planet) is a connoisseur of soap operas and saccharine romantic subplots, which the TV version smartly highlights. Apple TV+ surprised me with a thoughtful and creative adaptation of the books, diving deep into the group dynamics of the planetary research team—the TV writers even created, and solved, some messy “throuple” drama surprisingly well. In the books, Wells creates a believable and lovable cyborg with her creative exploration of neuroscience—“mixing brains and computer circuitry is not only science fiction,” there’s real science behind it, wrote Scientific American’s associate editor of mind and brain Allison Parshall in a recent article. Of course, the books are better than the show (aren’t they usually?). But the TV adaptation of these internal-dialogue-heavy novellas does Murderbot justice—or at least as much justice as can be expected within the Corporation Rim space sector. The online magazine Reactor published a brand-new Murderbot short story by Martha Wells on the same day the finale aired. —B.K.

Ends of the Earth: Journeys to the Polar Regions in Search of Life, the Cosmos, and Our Future

by Neil Shubin

Dutton, February 2025

The North and South Poles couldn’t feel more remote. But for Neil Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, they are both familiar and intricately connected to the story of planet Earth. Shubin, who co-discovered Tiktaalik roseae, a 375-million-year-old fossil of a hybrid creature, something between a fish and a land-living animal, has made a career of hunting for ancient signs of life at the poles. In his latest book, Ends of the Earth, Shubin gives a sweeping overview of how ice tells our cosmic history. For instance, geochemical analyses of the more than 50,000 meteorites gathered in Antarctica helped pinpoint the timing of the formation of the solar system. And fluctuating glacier size has dictated global weather and sea levels for millions of years. In fact, polar ice established ocean currents and wind patterns that led to variable weather conditions across East Africa millions of years ago. Some anthropologists believe that in adapting to such different environments, our ancestors developed larger brains and cognitive abilities. Most striking, though, is how quickly polar ice is currently changing, he says. “Our fragile window for understanding the cosmos, the planet, and ourselves is closing,” Shubin writes. —Andrea Gawrylewski

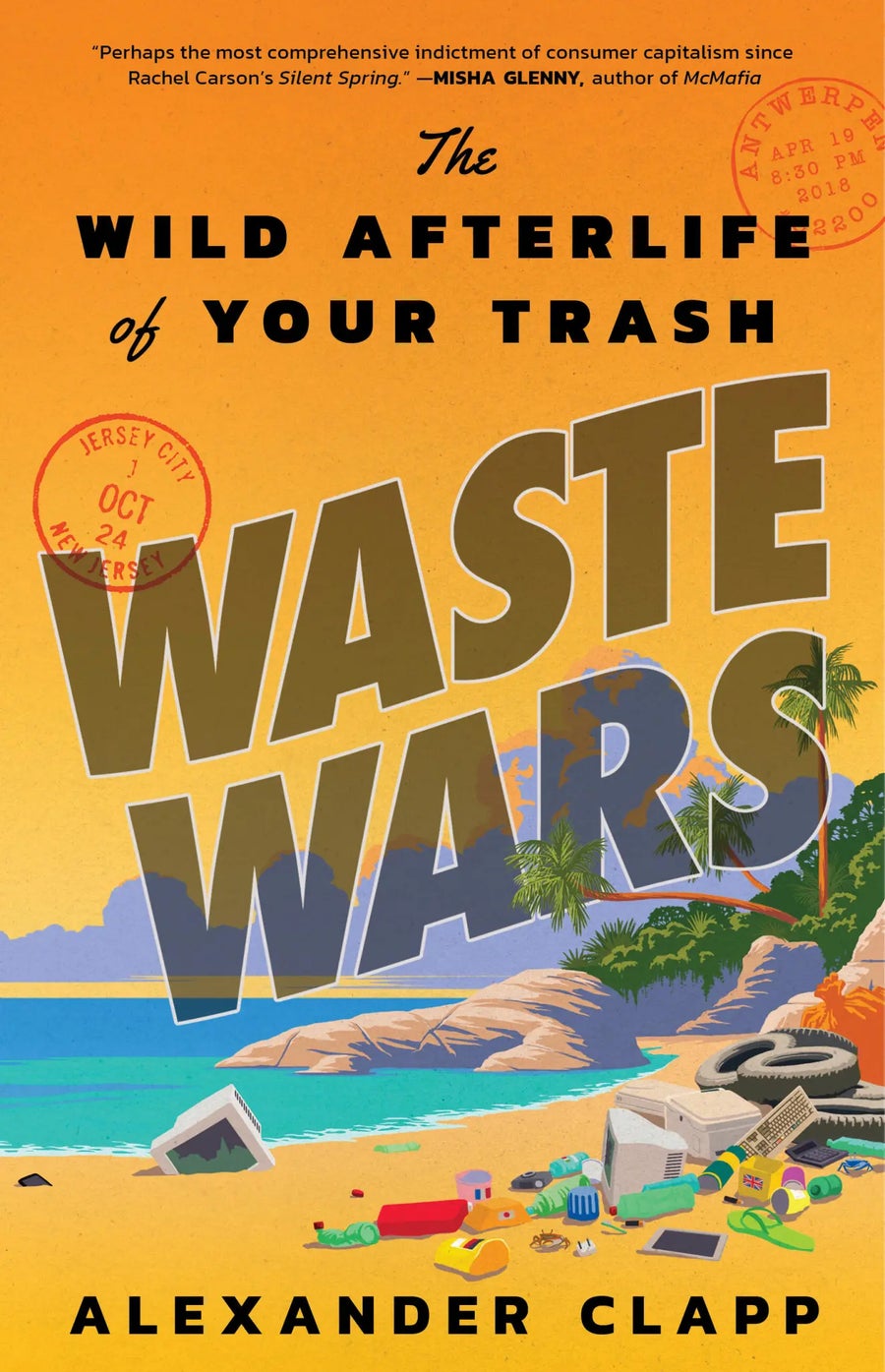

Waste Wars: The Wild Afterlife of Your Trash

by Alexander Clapp

Little, Brown and Company, February 2025

Billions of dollars are spent every year moving countless tons of trash all around the world in a waste black market—and no one knows exactly where it all goes or who is making a profit. Science journalist Alexander Clapp spent two years living out of a backpack in search of toxic dump sites hidden deep in unmapped jungles and traversing mountains of trash visible from space for his new book Waste Wars. “A lot of global trash over the last 30 to 40 years has been going to poor countries under the guise that it’s being recycled,” Clapp told Scientific American in a recent interview. But humans break down that waste in a lethal and dangerous process that releases toxic chemicals into the air and water, he said, and those chemicals disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations. “If you’re sending waste to another country, you’re not calling it trash on any export document—you’re calling it recyclable material,” Clapp added. “One thing that I hope my book encourages or leads people to question is how much of our waste is actually moving around the world.” —B.K.